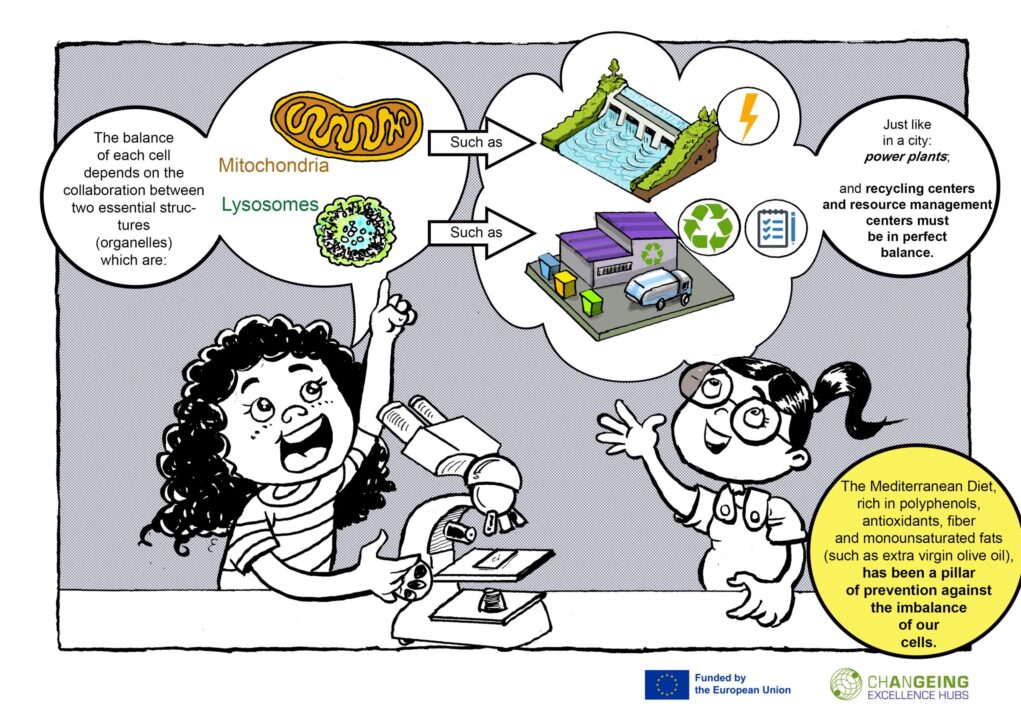

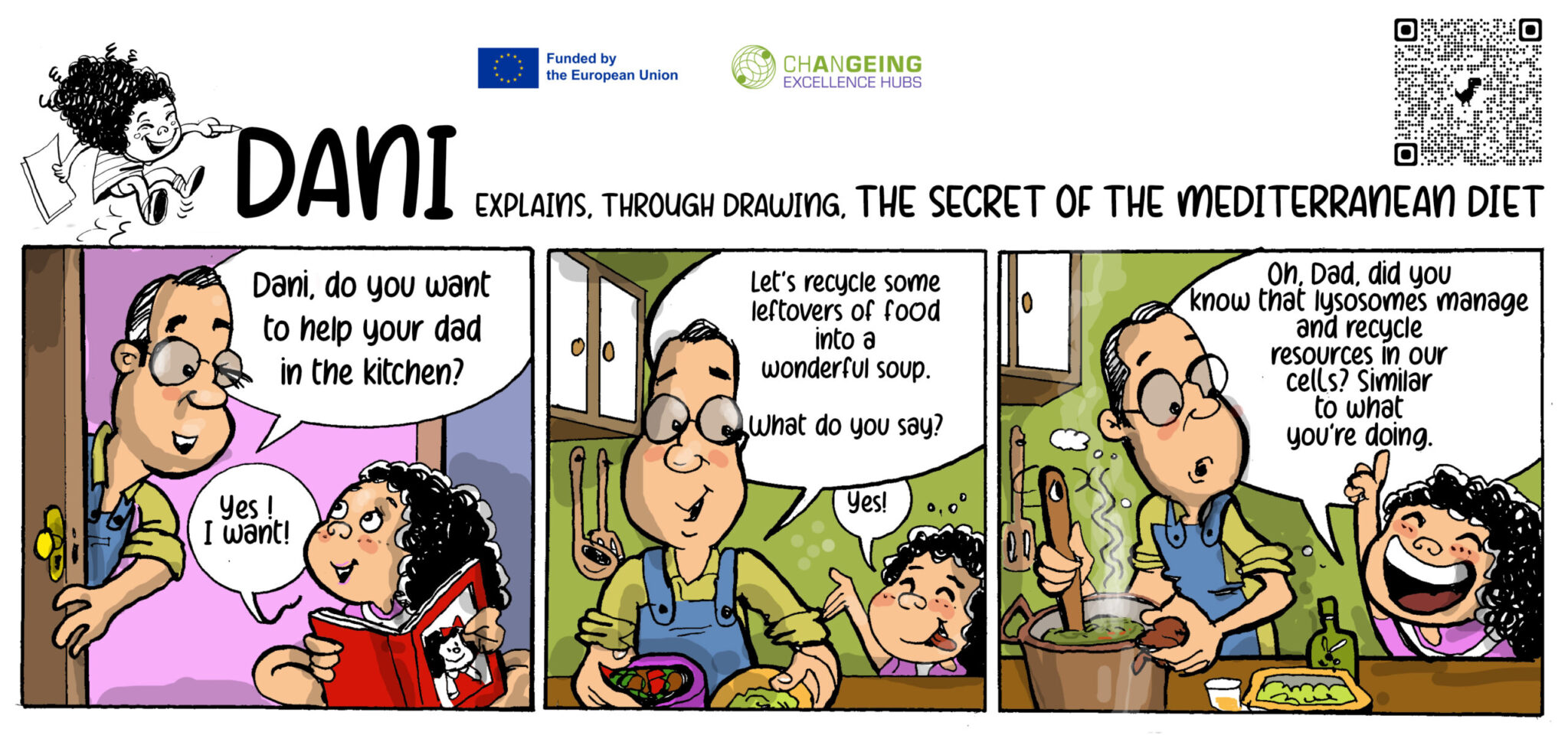

Within each of us, there is a universe of billions of cells. Each cell is an active, complex unit where life happens. Inside every cell, work is constant, and its balance depends on the collaboration between two essential structures (organelles): mitochondria act as power plants, generating the energy necessary for the cell to function; lysosomes are a recycling center that also serves as a logistics hub, detecting the inventory of some important compounds, and when they obtain them by digesting cellular “trash,” they deliver them to other cellular structures that need these compounds.

For a long time, science studied these two structures in isolation, each with its own specific function. However, as in any complex system, the health of our cells depends on the communication and synchrony between these two components. Recently, science revealed that the balance between mitochondria and lysosomes is fundamental to our vitality (1). When this coordination fails, it can lead to serious problems, including the development of diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

It is at this point of vital interdependence that the Mediterranean Diet comes into play. It is not just nutrition, but the ace up the sleeve that optimizes cellular infrastructure. The Mediterranean Diet provides increased capacity for infrastructure maintenance. Rich in polyphenols, antioxidants, fiber, and monounsaturated fats (such as extra virgin olive oil), this diet has been linked to improving the performance of mitochondrial power plants and strengthening the lysosomal recycling system. It is a cornerstone of prevention against age-related decline (2).

Imagine the mitochondrion (3) as the cell’s power plant, the furnace that transforms nutrients extracted from food into the vital fuel that allows the cell to function. Its structure, with folded inner membranes, resembles a complex architecture, optimized to capture and convert energy into ATP, the currency of life. Every movement, every thought, every memory, is powered by this energy.

The mitochondrion does not operate in isolation. Mitochondria belong to the cell’s large ecosystem, and their performance is dynamic: the power plants can fuse or divide, forming a complex network that adjusts to the energy needs of the cellular city.

In this scenario, the Mediterranean Diet (2) acts as an essential tonic for this power plant:

In the interstices of the city, the lysosome (6) operates with a different, but equally vital, intention. It is the recycling system and the guardian of cleanliness. Equipped with powerful enzymes, tiny biological “detergents,” the lysosome collects worn-out parts, damaged structures, and waste. With mastery, it transforms them into new materials, ready to be reused by the cell.

This process, autophagy (which means “self-eating”), is the cell’s way of renewing itself, of shedding the past to ensure the future. Without the lysosome, the cellular city would be suffocated by debris. The accumulation of waste would impede the flow of life, and the cell’s vitality would gradually be choked. Its function is the capacity to clean up what is not needed in order to renew and grow.

The role of the Mediterranean Diet (2) in lysosomal function (6) is crucial, albeit indirect:

The great secret revealed by science is that these two structures are not neighboring strangers (1). They move towards each other, meeting at contact points where their work becomes a “silent dialogue,” an exchange of information and energy. Mitochondria and lysosomes are interdependent partners, united by an invisible web of communication that is the pillar of cellular health. Harmony in this partnership is the guarantee of a long and healthy life for the cell.

It is at this point of contact that the cellular fate is sealed. The success of this coordination determines whether the cell lives in prosperity or enters a state of gradual decline, senescence (7).

As the years pass, just like the infrastructure of an aging city, the system can become less efficient. Time, genetics, or the environment can cause the dialogue to break down. Recent scientific research data shows that in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, the melody of life is going out of tune (1).

The loss of coordination between these two partners is not just a symptom; it is the very essence of these diseases. This internal failure, this imbalance in our cellular architecture, is now a central focus of research (1, 6, 7).

The discovery of this intimate and vital partnership brings new hope. Instead of focusing on just one of the organelles, science is now looking at the relationship, the workflow. The goal is not just to strengthen the mitochondrion or energize the lysosome, but to re-establish the dialogue between them (1).

In this search to restore the fluidity of the system, the Mediterranean Diet (2) emerges as a powerful intervention. By reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, and by supporting mitochondrial efficiency, it acts preventively, protecting the essential communication. It is a profound reminder that our health, and the health of our brain, are a reflection of a silent harmony that happens at a level we can barely imagine. Aging is not an inevitable destination, but a discoordination that science is trying to correct, often looking to ancestral patterns of life, like the Mediterranean diet, to guide our next steps.

Authors: Catarina Mendes and Nuno Raimundo

Design: José Gomes

Text: António Piedade

References

(1) Deus et al., Mitochondria–Lysosome Crosstalk: From Physiology to Neurodegeneration, Trends in Molecular Medicine (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2019.10.009

(2) Shannon et al., Mediterranean diet and the hallmarks of ageing, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2021) 75:1176–1192, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00841-x

(3) Lima et al., Pleiotropic effects of mitochondria in aging, Nat ure Aging (2002) 210 2:199–213, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00191-2

(4) Abir et al., Pharmacological potentials of lycopene against aging and aging-related disorders: A review, Food Sci Nutr. 2023;11:5701–5735, https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3523

(5) Zhou et al. Resveratrol attenuates endothelial oxidative injury by inducing autophagy via the activation of transcription factor EB, Nutrition & Metabolism (2019) 16:42, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-019-0371-6

(6) Tan et al., Lysosomes in senescence and aging, EMBO reports (2023) 24: e57265, https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202357265

(7) Martini et al., Cellular senescence: all roads lead to mitochondria, FEBS Journal (2023) 290:1186–1202, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.16361

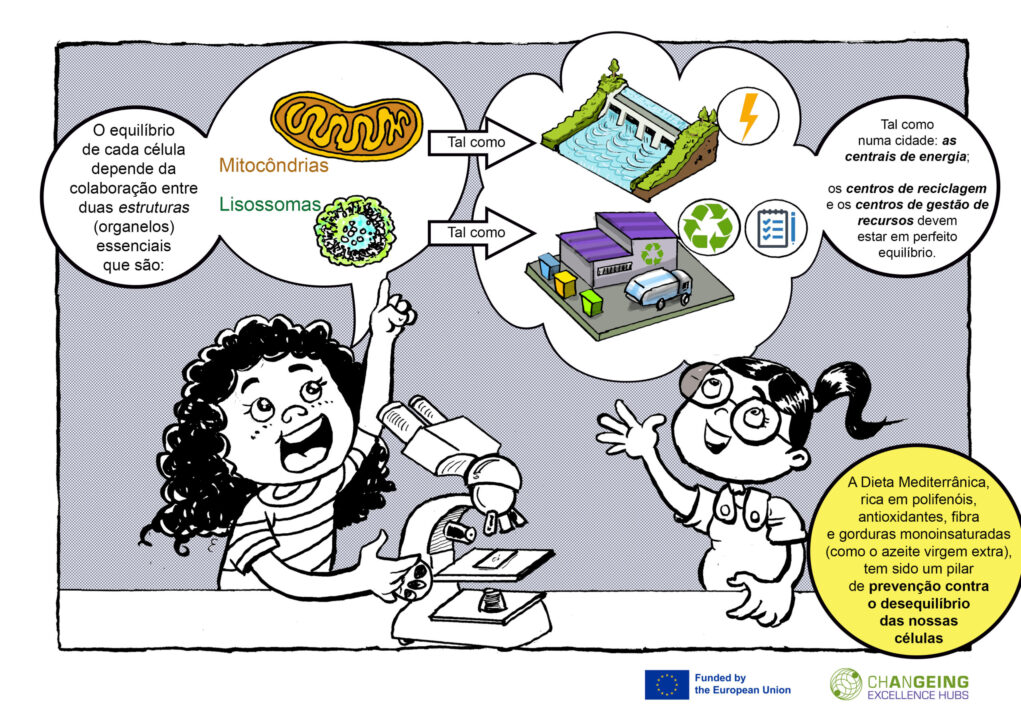

Dentro de cada um de nós existe um universo de biliões de células. Cada célula é uma unidade ativa e complexa onde a vida acontece. Dentro de cada célula, o trabalho é constante e o seu equilíbrio depende da colaboração entre duas estruturas essenciais (organelos): as mitocôndrias, atuam como centrais elétricas, gerando a energia necessária para o funcionamento da célula; os lisossomas, são um centro de reciclagem que também serve de central logística, pois detetam o inventário de alguns compostos importantes, e quando os obtêm por digestão de “lixo” celular, entregam-nos a outras estruturas celulares que precisam desses compostos

Durante muito tempo, a ciência estudou estas duas estruturas de forma isolada, cada uma com a sua função própria. No entanto, tal como num sistema complexo, a saúde das nossas células depende da comunicação e da sincronia entre estes dois componentes.

Recentemente, a ciência revelou que o equilíbrio entre mitocôndrias e lisossomas é fundamental para a nossa vitalidade (1). Quando esta coordenação falha, pode levar a problemas graves, incluindo o desenvolvimento de doenças como a doença de Parkinson e a doença de Alzheimer.

É neste ponto de interdependência vital que a Dieta Mediterrânica entra em cena. Não é apenas nutrição, mas sim o trunfo que otimiza a infraestrutura celular. A Dieta Mediterrânica confere mais capacidades de manutenção das infraestruturas. Rica em polifenóis, antioxidantes, fibra e gorduras monoinsaturadas (como o azeite virgem extra), esta dieta tem sido ligada à melhoria do desempenho das centrais elétricas mitocondriais e ao fortalecimento do sistema de reciclagem lisossomal. É um pilar de prevenção contra o declínio associado à idade (2).

Imagine a mitocôndria (3) como a central elétrica da célula, a fornalha que transforma os nutrientes extraídos dos alimentos no combustível vital que permite à célula funcionar. A sua estrutura, com membranas internas dobradas, assemelha-se a uma arquitetura complexa, otimizada para capturar e converter energia em ATP, a moeda de troca da vida. Cada movimento, cada reflexão, cada memória, é alimentado por esta energia.

A mitocôndria não opera isolada. As mitocôndrias pertencem ao grande ecossistema da célula, e o seu desempenho é dinâmico: as centrais podem fundir-se ou dividir-se, formando uma rede complexa que se ajusta às necessidades energéticas da cidade celular.

Neste cenário, a Dieta Mediterrânica (2) funciona como um tónico essencial para esta central elétrica:

No interstício da cidade, o lisossoma (6) opera com uma intenção diferente, mas igualmente vital. É o sistema de reciclagem e o guardião da limpeza. Equipado com enzimas potentes, pequenos “detergentes” biológicos, o lisossoma recolhe peças desgastadas, estruturas danificadas e resíduos. Com mestria, transforma-os em novos materiais, prontos a serem reutilizados pela célula.

Este processo, a autofagia (que significa “comer-se a si mesmo”), é a forma de a célula se renovar, de se livrar do passado para garantir o futuro. Sem o lisossoma, a cidade celular ficaria sufocada pelo entulho. A acumulação de lixo impediria o fluxo da vida, e a vitalidade da célula seria gradualmente asfixiada. A sua função é a capacidade de limpar o que não serve para se renovar e crescer.

O papel da Dieta Mediterrânica (2) na função lisossomal (6) é crucial, embora indireto:

O grande segredo revelado pela ciência é que estas duas estruturas não são vizinhas que se ignoram (1). Elas movem-se uma em direção à outra, encontrando-se em pontos de contacto onde o seu trabalho se torna um “diálogo silencioso”, uma troca de informação e energia. As mitocôndrias e os lisossomas são parceiros interdependentes, unidos por uma teia invisível de comunicação que é o pilar da saúde celular. A harmonia nesta parceria é a garantia de uma vida longa e saudável para a célula.

É neste ponto de contacto que o destino celular é selado. O sucesso desta coordenação determina se a célula vive em prosperidade ou entra num estado de declínio gradual, a senescência (7).

Com o passar dos anos, tal como nas infraestruturas de uma cidade envelhecida, o sistema pode tornar-se menos eficiente. O tempo, a genética ou o ambiente podem fazer com que o diálogo se quebre. Dados recentes da investigação científica mostra que em doenças neurodegenerativas, como a doença de Parkinson e a doença de Alzheimer, a melodia da vida está a desafinar (1).

A perda de coordenação entre estes dois parceiros não é apenas um sintoma; é a própria essência destas doenças. Esta falha interna, este desequilíbrio na nossa arquitetura celular, é hoje um foco central de investigação (1, 6, 7).

A descoberta desta parceria íntima e vital traz uma nova esperança. Em vez de nos concentrarmos em apenas um dos organelos, a ciência olha agora para a relação, para o fluxo de trabalho. O objetivo não é apenas fortalecer a mitocôndria ou energizar o lisossoma, mas restabelecer o diálogo entre eles (1).

Nesta busca por restaurar a fluidez do sistema, a dieta mediterrânica (2) emerge como uma intervenção poderosa. Ao reduzir o stress oxidativo e a inflamação, e ao apoiar a eficiência da mitocôndria, ela atua preventivamente, protegendo a comunicação essencial. É uma lembrança profunda de que a nossa saúde, e a saúde do nosso cérebro, são um reflexo de uma harmonia silenciosa que acontece a um nível que mal podemos imaginar. O envelhecimento não é um destino inevitável, mas uma descoordenação que a ciência está a tentar corrigir, muitas vezes olhando para os padrões ancestrais de vida, como a dieta mediterrânica, para guiar os nossos próximos passos.

Autores: Catarina Mendes e Nuno Raimundo

Ilustrações: José Gomes

Text:o António Piedade

Referências

(1) Deus et al., Mitochondria–Lysosome Crosstalk: From Physiology to Neurodegeneration, Trends in Molecular Medicine (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2019.10.009

(2) Shannon et al., Mediterranean diet and the hallmarks of ageing, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2021) 75:1176–1192, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00841-x

(3) Lima et al., Pleiotropic effects of mitochondria in aging, Nat ure Aging (2002) 210 2:199–213, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00191-2

(4) Abir et al., Pharmacological potentials of lycopene against aging and aging-related disorders: A review, Food Sci Nutr. 2023;11:5701–5735, https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3523

(5) Zhou et al. Resveratrol attenuates endothelial oxidative injury by inducing autophagy via the activation of transcription factor EB, Nutrition & Metabolism (2019) 16:42, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-019-0371-6

(6) Tan et al., Lysosomes in senescence and aging, EMBO reports (2023) 24: e57265, https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202357265

(7) Martini et al., Cellular senescence: all roads lead to mitochondria, FEBS Journal (2023) 290:1186–1202, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.16361

Soon will be available